Reconstructive Surgery Silvia Castro

Roger Lotchin is an urban and western historian. His writing

has centered on the history of nineteenth and twentieth century California

cities. He completed his Ph.D. in history from the Unversity of Chicago

in 1969. In 2005, he served as president of the Urban History Association.

Lotchin is currently a professor at the University of Northern Carolina with

courses in urban, World War II, and western history.

The west has always been a dream

land for foreigners to escape their troubles and gamble their ruined life in

exchange for instant success. Without the vast immigration of these

luck-speculators who brought expansion and a sudden market, San

Francisco would have most likely remained a

one-dimensional mission town: deserted and poor in its array of disorganized

culture. In a single decade, the Bay City came to be one of the most sought

after places to live because of its ¡§urban variety, diversity, and complexity¡¨

that welcomed all people who were looking to better their lifestyle.1

A city whose only history before the drastic urbanization was the

Mexican-American War exemplifies the difficulty of planning and deciding upon

the city¡¦s organized structure. No one was ready for the abrupt

population change. Starting off with a small population of about one thousand,

the small hamlet, after the Gold Rush, experienced an ¡§orgy of growth¡¨ that

would continue with the years as the city became more experienced from the

social camaraderie between residents to political appearances that would try to

terminate certain vices.2

Embodied in Roger Lotchin¡¦s San Francisco 1846-1856 From Hamlet

to City, the city became a port of new ideas, causing an influx of people

awaiting to make their mark on this untouched bay city.

At the beginning of the book, the

author illustrates the malfactors of the poorly developed settlement in 1846.

The Mormons who first occupied the lands in the 1830¡¦s were the only ones who

brought any significant expansion to the bay, and even then, the augmentation only

colonized a little under nine hundred of these religious residents, not enough

to commercialize the area with trade benefits. Even the Gold Rush brought few settlers

who wanted to permanently stay; therefore, building a municipal society was

difficult. But as people poured into surrounding areas, such as Stockton

and Sacramento, a friendly

competitive atmosphere emerged. Clipper ships needed to transport goods to

populated and enriched cities, but the narrow and shallow waterways proved this

task to be impossible. However, fortunately for Yerba Buena, San

Francisco¡¦s original name, this problem was the spark

plug that would jump start the town¡¦s financial system. The ships had to reload

their cargoes onto smaller boats, and the Bay City

became the ¡§beneficiary of a transportation break in the gold min[ing]

commerce.¡¨3 Communication and transportation developed

within the city. Jobs became more abundant, but the enormous rate of interest

revealed the difficulties of the weak banking structure. Private hiring

exchanges like the YMCA ¡§maintained employment agencies¡¨ to ease the burden of

debt.4 Heavily relying on outside help for investment loans, more

men began to petition the expansion of the city¡¦s manufacturing system. Soon

enough, a broad number of individual or small groups of industries rounded out

the industrialization of the city, such as ship building, food processing,

wharf construction, and flour mills. With the increase of population and the

flux of prosperity, social distinctions also increased and segregation emerged

because of the residential zoning districts where the working class migrated

towards Market Street,

living closer to their work. By the mid-nineteenth century, the urban people

began to adapt to their environment and started to care about the business,

politics, and social composition of their soon-to-be home.

The transitory nature of the early

society, the skewed demographics, and the boom and bust nature of the economy

led to a culture that was peculiar to San Francisco.

During 1848, San Francisco was

still a rootless community with no real native residents. Americans, even

though most were not locals, welcomed foreigners to San Francisco and

experienced a feeling of camaraderie among residents, yet they did expect the

immigrants to ¡§conform to certain American standards and values¡¨.5

At first, they opened their arms to foreigners from western and northern

Europe, but they quickly displayed a racial hierarchy. For example, many

Americans thought all Australians were disgusting ex-convicts. Residents

preached a melting pot society but rarely practiced toleration. Slowly and

surely, they maintained their aloofness towards the African, the Chinese and

Latin Americans. While keeping stereotypical perspectives of each group, they

referred to Latin Americans as ¡§greasers¡¨ and saw them to be nothing more than

¡§shiftless, dirty, cruel and lazy¡¨ beings.6 As

economic factors shifted, tolerance for diversity shifted as well. Because

of peoples¡¦ relocation from eastern United

States to the west, integration occurred

within isolated regions¡Xlike southerners and Yankees. Schools became a safe

cultural community where children were exposed to others of different

backgrounds in a positive way and learned each others traditions. Children grew

up with a sense of difference, but not realizing whether difference is bad or

good¡Xbut just an understanding that other races existed. However, constant competition between housing and job wages impeded

the gentle welcoming in the United States. The former hamlet became a battleground where

families had to decide whether to stay and learn to call this place ¡§home,¡¨ or

leave and go back to their familiar abodes. On the fence, many miners finally

decided to stay and bring their family, because they were optimistic and felt

that success was near.

With no sophisticated police force

or judiciary system, the crime rate increased. In the years after 1848, the

¡§rascals multiplied and the notoriety of the city grew apace,¡¨ because of the

temptation from the lack of consequences, since the weak court system often

delayed cases.7 The Vigilance Committee of 1856, consisting of

average civilians who were concerned with the reputation of their community,

quickly re-shaped San Franciscan police force. It helped reform San

Francisco politics by attacking political corruption,

and brought the People¡¦s Party (populists) to power. The Vigilance Committee

also reformed gender politics in San Francisco

as well. Before the committee had a strong influence, middle-class American

women arrived in the city ready to become active in their new community, and

they gained a prominent place in public political discourse in San

Francisco. Their opinions were sought out, listened

to, and debated by other women and men. However, soon afterward, the vigilantes

started to set the agenda, not only for the summer of 1856 but for years

afterward, and that agenda consisted of politics in deeply masculine terms.

Vigilantes, who excluded women from committee headquarters and increasingly

ignored or refused to print women¡¦s letters in the newspapers, created a

political climate in San Francisco

that was anything but conducive to women¡¦s political activism. Perhaps, then,

it is not surprising that no woman suffrage organization existed in San

Francisco until after the Civil War and the demise of the People¡¦s Party.

In the second half of the novel,

representing also most of the second half of the decade, Lotchin depicts

women¡¦s significant role in society outside of politics. The presence of women

was not only a family concern, but a public concern because the women would

¡§lend stability and improve the quality of urban life.¡¨8 The climate

had changed dramatically from an area where men with picks in their hands lived

miles away from their families, to a modernized city where women became

involved in every aspect of life. These wives who came from the east were set

to transform the bay into a safe and appropriate habitation for their family.

The immoral climate had changed from 1846. Women joined with the support from

the press to petition prohibition. People changed their mindset about gambling

and prostitution after reading about the Cora case in the newspapers, which

involved two men arguing inside a theatre because one man, Charles Cora, was

insolent enough to invite a prostitute, Belle, into the public building, where

James King of William felt uncomfortable having his wife sit in the presence of

a whore. The public attention from the case represented the conservative shift:

the Bay City was no longer a toy

store for men to run around, but now a home to share the love between family

and friends. San Francisco

constantly kept in mind the general welfare of the community as its ultimate

goal, but ¡§the means¡Xdemocracy, liberty, or progress¡Xvaried.¡¨9

Lotchin takes pride in the rapid

growth of the ¡§instant city¡¨ that was able to come together and prove that even

though its early history did not supply a solid foundation, it still bred a

prosperous metropolis.10 The cultural, political, and social changes

shifted with the people and surroundings, accommodating the residents of the

cosmopolitan city, where everyone differed from wage earnings, to religious

background, to marital status. He tells the history mostly chronologically with

different perspectives from people moving into the city. Lotchin also shows

that if the people voiced their opinions, their wants, and their necessities,

they could produce the city that they never thought would be home. San

Francisco would grow in number and economy with the

United States Mint and assay offices, and garner much wonder and awe from the

eastern side of the country.

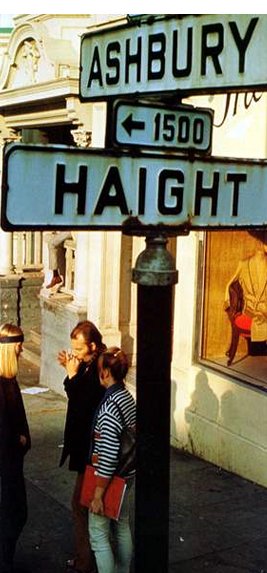

San Francisco 1846-1856: From

Hamlet to City was written in the early seventies, at a time when hippies

had already made their mark and ¡§peace¡¨ was the saying to shout wherever and

whenever. Lotchin was influenced by an era when people did not trust their

government. Following the end of the Vietnam War, people at that time wrestled

against the government and petitioned for reform, expressing what was best for

the American people, not just for the country¡¦s foreign policy. Lotchin is a

social and political historian who focuses on the wants and needs of people

living in San Francisco to show how

successful the development was compared to the initial assumption of the residents.

Originally that city had no systematic city government, though the fault did

not lie within the administration, since no previous management existed in that

bay before 1846; San Francisco had

no history. It was only a ¡§drowsy hamlet of 1846 or the frantic, makeshift town

of 1849.¡¨11 But within a century, San Francisco

grew to be a bustling conurbation at the heart of the state¡¦s commerce.

Two scholars share similar

perspectives on behalf of Lotchin¡¦s work. Both critics, Roger Simon from Lehigh

University and William Mulligan representing Eleutherian Mills-Hagley

Foundation, praise Lotchin¡¦s careful breadth of the traditional urban biography

which covered that decade in ¡§exhausting comprehensiveness¡¨.12

Admiring his theme as the city¡¦s struggle to establish ethics, Simon observes

the authors persistence in showing the competition between public and private

matters, but Lotchin falls short to recognize which parts of San Francisco had

more than just a local identification. There is little to no connection to

surrounding states, which is significant because of the Golden Gate

city¡¦s vast economy. Also, mentioned by Mulligan, Lotchin¡¦s book does not

succeed in its thorough elucidation of the economic factors behind San

Francisco¡¦s growth, leaving out major industrial

projects. However, overall, both reviewers extol the book as a better way ¡§to

understand just what urbanism [is] and what it demand[s] of urbanites.¡¨13

Lotchin¡¦s criticisms seem valid; California

was but a deserted place only occupied by Spanish missionaries and Native

Americans. Constructing the foundation of a whole city in only ten years,

especially when people come from all over and differ in viewpoints and

religious background, would be difficult, if not unattainable. San

Francisco was a cosmopolis where new ideas were

exchanged and quickly people predicted its richness, years before it would

become prosperous. However, Lotchin fails to supply enough information on the

relationship between the national government and the city government, especially

lacking information about the shift from territory to state. Lotchin focused

his perspective more on the surrounding areas and less on the relationship to

the United States.

For example, Lotchin never addresses why the state petitioned for statehood and

how it changed the governing body of San Francisco.

The southern cities like San Diego

and Los Angeles are never mentioned

a comparison between cities that could have allowed a deeper analysis of the

cities¡¦ rise from the Spanish culture to a more diversified society. Lotchin

discusses the San Franciscans and the diversity that they brought from foreign

countries, rather than the immigration of New Englanders and southerners. The

reader therefore understands that San Francisco has been a ¡§world city from the

very beginning¡¨.14 However, it would have been more educational if

Lotchin had expanded the time period a little over a decade or gave a synopsis

of San Francisco in its later years, in order for people to link the effects of

each change to an event in the city¡¦s future.

California,

with its booming cities that emerged from the Gold Rush, had proved to the

federal government that an investment in statehood would be beneficial to the

country. With the dream of Manifest Destiny, railroad companies longed for the

passage to the Atlantic Ocean and California

made that dream come true. Many in the Eastern United States,

especially poor white men in the South, like the Know-Nothings who rallied for

free labor, sought after the abundant farmland that eventually produced

millions of barrels of wheat. Especially after the Panic of 1837, families all

over the country wanted to leave the economic turmoil and try to lead a

prosperous life. Looking for peace and stability, many people saw California

as a haven. People came from all over the world, unlike other cities, for

example, New York, where all the

Germans gathered together in their own secluded communities. California

was a home to all: here they could work together and play together, with some

collisions like any other nineteenth century city. San Franciscans refused to

depend on the help from other states; it had ¡§agricultural products from Latin

America, flour from Richmond,

silk from China,

ice and apples from Boston, coffee

from Java, oranges from Tahiti,¡¨ but this was not enough

for the American city, it didn¡¦t want help.15 It wanted to

illuminate its economic status by itself.

The people in the eastern United

States saw California

as a local accomplishment. But the author differs from them and instead, views California

as an ¡§international project.¡¨16 These selfish citizens saw the

municipality as a money-making machine, a trading ship to help the nation

economically and socially. It was their door to the Far East,

an easier route to negotiate and trade with China.

Its history connected the United States

with Latin America, so that they could continue to have

a dominant role in foreign policies. Their statehood was a warning to Mexico,

that they were expanding and powerful. Lotchin sees California,

most importantly, as a diffusion of people and gives them credit for modeling

to the rest of the country the diplomatic aura that can exist between an array

of people. Compared to the east coast, California

was where people maintained their laid-back personalities while co-existing

with others and experiencing the ¡§era of good feelings,¡¨ a time where residents

looked back to the primitivism of the state and the success that had been

achieved and searched with optimism, for more progress in the near future.16

It took only a decade to build the vast city where people had

come to the Golden Gate with ¡§heads full of general rules¡¨ and where many

endeavored to ¡§reconcile the claims of different and contrary values¡¨.16

San Francisco didn¡¦t find the people; the people found San Francisco. Now, it

is a home, a business, and a social network where ¡§each institution, each

group, and each practice in the city justified itself in terms of its value to

the generality¡¨ and focused on the community before the individual.17

1. Lotchin, Roger W. San Francisco, 1846-1856: From Hamlet to

City. New York: Oxford University Press, 1974. 277.

2. Lotchin, Roger. 9.

3. Lotchin, Roger. 6.

4. Lotchin, Roger.

85.

5. Lotchin, Roger.

106.

6. Lotchin, Roger.

112.

7. Lotchin, Roger.

279.

8. Lotchin, Roger.

304.

9. Lotchin, Roger.

342.

10. Lotchin, Roger.

136.

11. Lotchin, Roger.

xix.

12. Simon, Roger.

¡§The Journal of Economic History.¡¨ JSTOR. 29.2

(1981): 746-747. 2 June 2008 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/17950>.

13. Mulligan,

William. ¡§The Journal of Economic History.¡¨ JSTOR.

40.1 (1980): 208 209. 2 June 2008 <http://www.jstor.org/stable/2120468>.

208-209.

14. Lotchin, Roger.

vii.

15. Lotchin, Roger.

vii.

16. Lotchin, Roger.

301.

17. Lotchin, Roger.

345.